700 Years of Medical History: An Interview with Pamela Forde of the Royal College of Physicians

January 29, 2025

January 29, 2025

From piecing together the Dead Sea Scrolls with sellotape to digitizing a 19th-century scroll from a Japanese acupuncture school, the world of conservation is full of fascinating stories. We sat down with Pamela Forde from the Royal College of Physicians (RCP) to get the inside scoop on an archive dating back to the 1200s and to learn more about the art and science of preserving history.

Pamela Forde managed modern records before returning to historical ones, where the RCP’s long-stretching history caught her eye. She has been an Archive Manager with the professional membership body for over 21 years and counting.

Forde: One common misconception is the idea that conservation consists of preserving an original item intact. Conservation may remove original material that's been worn or damaged too much and replace it with a modern copy, which means that the item can be handled safely. So, although you can keep the pieces that have been removed, that item is no longer as originally produced. Modern best practice keeps removal to a minimum and does its best to make changes which can be reversed because one of the things that we don't always know is the long-term effects of time on a particular material or chemical.

A very famous example is the Dead Sea Scrolls. At the time they were discovered, sellotape was a brand-new material, and seemed perfect as a backing material for piecing the fragments together again. Now modern conservatives are spending decades removing these very fragile fragments from the glue and the sellotape. We don’t necessarily know how material is going to change over time, so modern conservators try to make changes that can be easily reversed.

In our collection we have 13th-century handwritten books, and when we had to have those rebound, because the original bindings were disintegrating, we picked a conservator who used the same materials and techniques the original binders would have used. The new binding for these 1300s manuscripts is from the 1950’s but uses the same materials and techniques the binders in the 1300s used.

Forde: An unusual piece would be a really lovely 19th-century Japanese acupuncture school text. It's a continuous scroll with beautiful images of the male and female body, showing the acupuncture points. This is a very unusual item for a Western collection. In the west books are bound by cutting paper into rectangles. You sew the rectangles together, forming a block and you sew the block to a spine that sits between two boards.

A scroll is literally one continuous piece of material that's wrapped around a central rod. Very different to western book binding. The conservation needs and requirements for a continuous scroll which you unroll to the page that you’re looking for and then roll to close, are very different.

In term of the digitization, it was challenging because with a Japanese text you read from right to left. It had to be imaged in sections and reassembled as a continuous roll, for reading in the opposite direction to European text.

Forde: As far as I’m concerned, all the items are valuable. The information they contain and what they can tell us about our history and the history of medicine are genuinely unique. They're usually the only copy of that item anywhere.

A good example of a unique item which is valuable in so many cultural ways, is an original Charter from Elizabeth I. It was a legal document which allowed the 16th-century college to take the bodies of up to four executed criminals from the scaffold at Tyburn, to make anatomical dissections so they could study and teach on anatomy. In the 16th century, most people wouldn't leave their body to medical science for dissection. So, there was a huge shortage of bodies for dissection.

For executed criminals it was considered part of the punishment of execution that you would be dissected afterwards and your body wouldn't remain intact for burial.

Forde: I like letters because letters are very personal things. Some are written in a professional capacity, but other letters are written in a personal capacity to friends, family and they really give a sense of personality. For example, we have about 15 or 16 letters from Edward Jenner to a friend. He's a famous figure in the history of vaccination. But his letters to his friend give a really strong sense of his personality.

View now (with institutional access or a free trial):

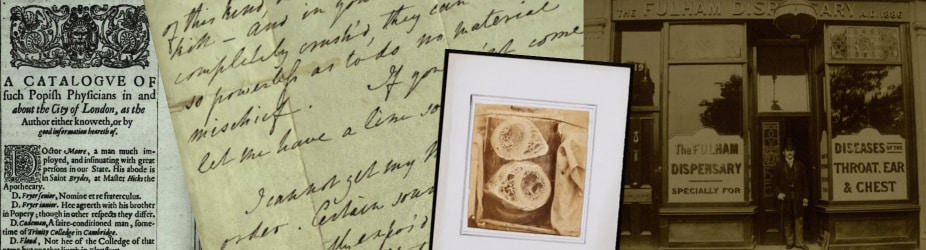

Autograph letter from Edward Jenner to Dr John Baron, 1821. Edward Jenner, Autograph Letter Sequence. Source: The Royal College of Physicians archive.

Forde: Modern science knows a lot. It doesn't know everything yet, and it's sometimes still proven wrong. Being wrong restores a sense of humility, when you had a tendency to think that you've discovered everything. Studying all of the mistakes that we made in the past, as well as the true discoveries, I think, encourages an attitude of “let's not take anything for granted. Let's examine everything. Let's not make assumptions.”

Some past medical advances and breakthroughs have never been bettered. Medical practitioners in the Golden Age of Islam in the Middle East discovered, by experience, diagnostic symptoms of certain diseases that are still modern standards. William Harvey was one of our members in the 1600s. The repeatable experiment in his book De motu cordis, is still something which you can use today to demonstrate the fact that the heart is a pump, circulating blood around the body. So, the past is not necessarily superseded and can tell us a lot about how we came to where we are. Studying the past can point towards clues for future discoveries.

View now (with institutional access or a free trial):

Eleven letters of William Harvey to Lord Fielding

William Harvey, F. J. Librarian, Harvey, William, 1636-1912.

Source: The Royal College of Physicians archive.

Forde: I’m an archivist. I do think that there’s nothing that compares to holding a piece of history in your hand. That being said, that piece of history could be tiny. It could be a huge elephant folio. It could be in fragile condition. One benefit of digitization is that original size generally doesn't matter. You can look at any piece of material from the smallest item to the largest and you can fit it onto your screen, and you can enlarge it for small handwriting. You can zoom right in to make the illegible and difficult to use easy to access. Very important.

For things that are fragile, you can examine them fully, digitally, in ways you cannot do physically anymore.

Forde: No problem. Thanks, Meghan.

Experience digitization first-hand with Wiley Digital Archives, a platform built for researchers. Unlock advanced features like keyword search, translation into over 100 languages, and Automatic Text Recognition (ATR) software that deciphers challenging handwriting. Travel through over 700 years of historical medical research with a free trial, or read more, including 5 approaches to medicine and remedies as they appear in the archives.