The Woman Who Fought Machetes with Trees: Wangari Maathai

March 05, 2025

March 05, 2025

In 1999, Wangarĩ Maathai and about 20 of her supporters were attacked by approximately 200 security guards. Their crime? Planting trees in a public forest cleared by real estate development.

Wangarĩ Maathai was born on April 1, 1940, in Ihithe, Kenya. She belonged to the Kikuyu ethnic group, the largest ethnic group in Kenya, comprising almost 20% of the country's population. In the 1940s, it was rare for girls to attend school in Africa, but Maathai challenged societal norms by pursuing an education with her brothers. She excelled, earning a scholarship through the Kennedy Airlift program to study biology in the U.S. and later becoming the first East African woman to earn a Ph.D. at the University of Nairobi.

Committed to environmental and social justice, Maathai founded a movement that empowered women to combat deforestation by planting trees. Despite facing multiple arrests for her activism, she remained unshaken and determined, making history in 2004 as the first African woman to win the Nobel Peace Prize.

When Kenyan women raised concerns about local environmental challenges, including a diminishing food supply, hardships collecting firewood, and shrinking streams, Maathai responded by founding the Green Belt Movement (GBM) as part of the National Council of Women of Kenya (NCWK). Established in 1977, it advocated for forest protections against threats like land grabs and agriculture. The result? A legacy of over 30 million trees planted and a movement that reshaped conservation in Kenya.

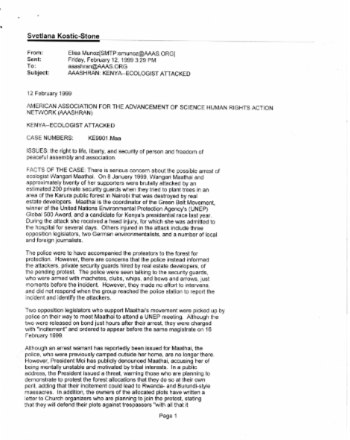

The New York Academy of Sciences archive, as part of Wiley Digital Archives, includes a detailed report of a human rights transgression against Maathai. On January 8, 1999, Maathai and protesters headed to the Karura public forest in Nairobi to plant trees. Police accompanied them, but their protection proved seemingly hollow, as they were seen conversing with security guards hired by real estate developers —guards who soon attacked Maathai and her supporters with machetes, clubs, whips, and bows and arrows. The police made no effort to resolve the situation and offered no response when the group reached the police station to report the incident.

While police camped outside Maathai’s house, President Moi dismissed her as “mentally unstable” and accused her as having tribal motivations—tactics meant to discredit a growing movement. Furthermore, Moi warned that all who dared protest would do so “at their own peril,” adding that their incitement could lead to Rwanda- and Burundi-style massacres.

Our records from the Committee on the Human Rights of Scientists show a widespread response that vouched for the freedom of Maathai and all those associated with her movement who were arrested.

View the case on Wiley Digital Archives (with institutional or free trial access):

Wangarĩ Maathai faced many hardships throughout her life but never backed down. She rose to become an assistant minister of the environment, only to be dismissed by the ruling party due to her involvement in opposition politics. Her personal life was also met with challenges—her husband divorced her, claiming she was “too strong-willed.” Despite the setbacks, Maathai remained dedicated to her cause. Even in death, she upheld her principles, requesting not to be buried in a wooden coffin as a final act of environmental consciousness. And according to the United Nations, Nigerian environmental activist Nnimmo Bassey commented, saying, “if no one applauds this great woman of Africa, the trees will clap.”

Empower your team’s research with a free trial of Wiley Digital Archives and champion underrepresented histories or dive further into stories from our archives.